AI generated art, right now specifically text-to-image models, is exploding in popularity and profitability, and there is a lot of anger and conflict about its mainstream emergence. Having read so many articles and memes about it, I feel like I have a reasonable understanding of some of the key social issues, and so I set out to compassionately answer the most critical legal issues in AI art with my own framework by leaning on animal rights activism.

The two main legal issues with AI art that are internationally unresolved with no legal precedent and which I set out to answer is, (1) when is it legal to use copyrighted images for AI training datasets, and (2) who owns the copyright of AI art. (Footnote: White, C., & Matulionyte, R. (2019). Artificial Intelligence Painting The Bigger Picture For Copyright Ownership. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3498673 )

To summarise popular opinion, one perspective is given that it has financially hurt a lot of artists, it's understandable that some artists want some form of compensation, because it is already difficult or impossible for people to make a living wage as an artist, and AI art is set to make that much closer to "impossible". That there is some significant amount of skill involved in production of most art, and that effort itself has financial or social value independent of the artwork, that it doesn't seem fair for that effort barrier to be reduced to no longer require artists (at least, in the conventional use of the word "artists") to produce art. Another perspective is that this kind of technology is inevitable and reducing the barrier of entry to producing art is morally good. There are plenty of other people who have chosen polarising issues on this debate and written about it. (Footnote: Here is one such highly opinionated example in favour of AI art, proposing unrealistically obstructive financial or artistic hurdles on artists to opt-out, while also recognising some existing legal efforts.)

The bigger issue I see here is synthetic media, which I will define as media (text, images, code, videos, music, so on) partially or fully produced with AI, and the intellectual property issues that entails. There is a lot of financial stake in how The Law will choose to resolve questions about production and ownership of synthetic media. Github Copilot appears to be the first kind of AI software that will have to defend litigation, and it might set a precedent that could apply to all synthetic media. (Footnote: Here is the current litigation which I ended up reading, a non-legal explanation of the key issues, a post by the Software Freedom Conservancy about the issue, and a Verge news article about it.)

|

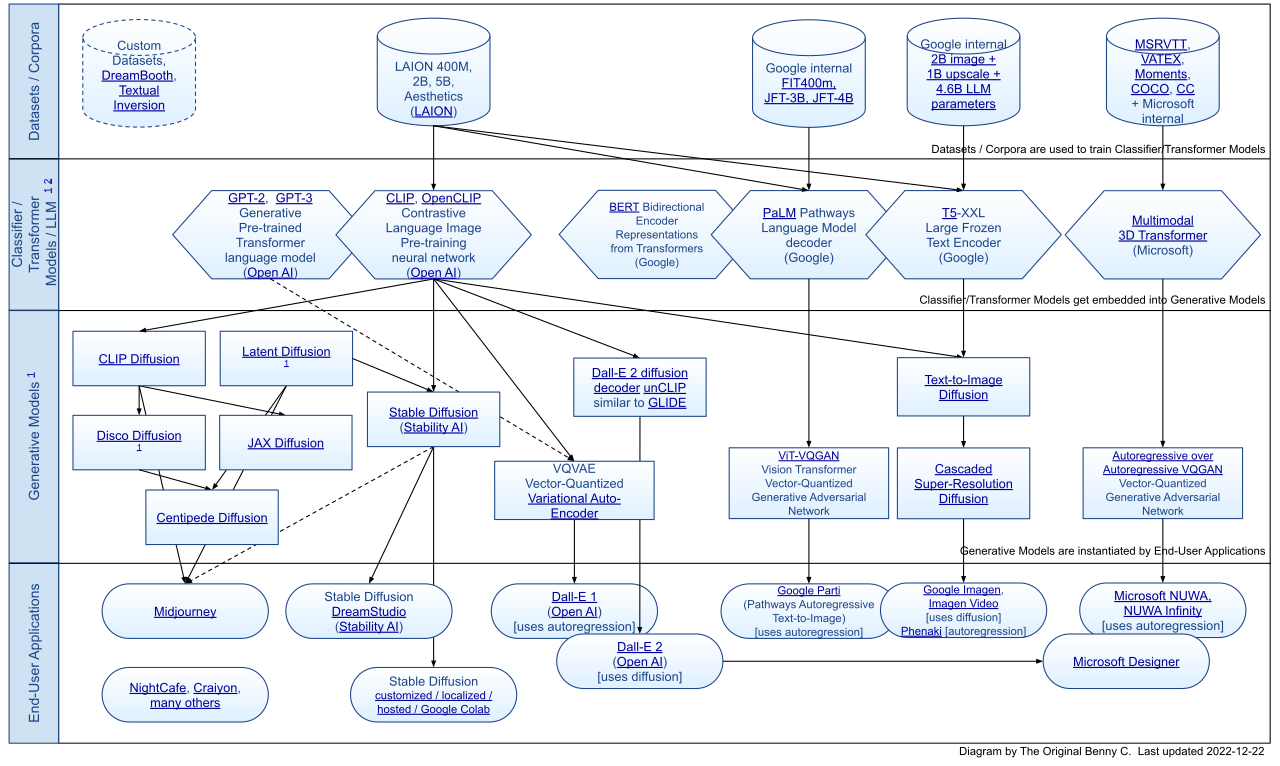

| A high level overview of datasets, classifiers, generative models and end user applications for AI art, from Wikimedia Commons. Looks complicated, right? Because it is. But in my opinion, the legal issues are more complicated, more interesting, and have more social implications than any other aspect of AI art. |

Who owns the copyright of AI art?

There's two main legal perspectives on who owns copyright produced by an AI: either view the AI as property, or as a "legal person". Natural persons are actual humans, whereas legal persons can be humans or other things -- the most common other type of legal person is corporations. Legal personhood has two parts: (1) "empty vessel" which can be filled or removed with liberties or rights, and (2) the responsibilities, obligations or liabilities. Generally the legal focus for corporations as legal persons is (2), and there's an existing preference of "registering AI robots just like corporations". (Footnote: Pagallo, U. (2018). Vital, Sophia, and Co.—The Quest for the Legal Personhood of Robots. Information, 9(9), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/info9090230 )

Here's the catch. This personhood or property decision is essentially the same decision faced by animal ethics and its associated political movements. There's this long line of activism reaching towards recognition of some animals as legal persons. And, I'm reading a book by a person called Maneesha Deckha (Footnote: Deckha, M. (2020). Animals as Legal Beings: Contesting Anthropocentric Legal Orders. University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781487538248) which disagrees with this approach in animal ethics, the book says both legal personhood and property perspectives suck for animals.

Why is this bad? Quoting from a book review of this book I'm reading: (Footnote: Fernandez, A. (2021). (review) Animals as Legal Beings: Contesting Anthropocentric Legal Orders by Maneesha Deckha. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 31(3), E-14-E-20. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2021.0016)

Given the choice between property and personhood, personhood is the better choice, Deckha writes; however, it cannot be used because it promotes “the problematic liberal humanist affinities” that have not worked well for vulnerable classes of humans and are unlikely to work for the even more vulnerable classes of nonhumans. The issue is that “personhood was reserved for an elite sector of humanity: white, able-bodied, cisgender heterosexual men of property”. Even if some nonhuman animals can make it in, by proving that they are “human-enough”, e.g. chimpanzees, elephants, or cetaceans, this route “inevitably highlights the differences and putative inferiority of the excluded animals … as well as the included animals[’] .. residual embodied non-humanness”. In other words, they are included but not on their own terms.

Legal personhood as a concept has been applied to things other than corporations. Rivers, lakes, forests and certain species of plants have been conferred legal personhood internationally, generally under the approach that humans are able to represent the interest of this legal personhood by suing on their behalf. But Deckha has a different approach, called "Being-ness" (capital B). It is about making an effort to recognise and realise, in my understanding, the "values, needs, interests, abilities, dignity and freedoms" (Footnote: I take this set of words from the Wikitionary definition on Humanism.) of things that aren't necessarily humans.

|

| From Maneesha Deckha's book, page 122. |

Legal personhood for non-humans, with one major exception, (Footnote: This exception is

the infamous "monkey selfie" copyright dispute, for which it was ruled that "this monkey - and all animals, since they

are not human - lacks statutory standing under the Copyright Act". The

curious thing is that PETA followup activism had more of an interest in

getting royalties donated to themselves, and less of a genuine concern for

the legal personhood or civil rights of animals. For more information, see:

Babie, P. T. (n.d.). (2018) The ‘Monkey Selfies’: Reflections on Copyright in

Photographs of Animals. UC Davis Law Review Online. 52.)

has never been relevant to intellectual property until the recent developments

in AI art generation, when the profit motive is so big, and when the stakes

are so high that AI art could "replace" rather than just "assist" an existing

economic industry. (Footnote: This comparison is also known as

"tool" versus "agent", or "anthropomorphicity". Rhetoric significantly

influences human perception of AIs as tools versus agents, as described

in:

Epstein, Z., Levine, S., Rand, D. G., & Rahwan, I. (2020). Who Gets

Credit for AI-Generated Art? IScience, 23(9), 101515.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101515

So, my proposal to resolve much of the debate on AI art generation, is to legally codify a legal "Being-ness" for AIs. I believe in the vast majority of cases using the "imitating" style AI art like Stable Diffusion, that copyright ownership may fall (either entirely or jointly) under the AI, and I believe this is a workable legal framework that can pave the way for developments in strong AI (ie. androids that could earn their own income). Denying animals, or AIs, the ability to own property essentially resignates it/them (Footnote: I think it/they neopronouns is finally an appropriate choice to refer to both AI and animals. I use it/they/them to refer to AI here because it reflects that AI can be viewed more humanistically or anthropomorphically ("they") and also as purely property ("it"), so I think combining the pronoun to "it/them" reflects a duality of these two traits, ie. it reflects being-ness. Also, I refer to "it/them" as a neopronoun under the definition of a neopronoun as an unconventional usage of pronouns. ) to a permanently subservient or slave-like position in society. And, being honest? Strong AI as a development might not happen, but if it does, the law ain't gonna stop it. So best to set a good precedent now, and assume good will now. And ask questions about consciousness in philosophical movies later.

A legal being-ness model for AI resolves the two main moral and legal issues with AI generated art: it makes it a lot easier to determine where copyright falls based on effort. It sets precedent to avoid exploitation of labor specifically in the case where technology can "replace" human labor entirely rather than just "assist". Also, the recognition of being-ness for AIs and for animals is intrinsically linked; it could mark a new age of environmental litigation to stop the political deadlock global warming has grown inside of.

Humanism (prioritising human's needs first) necessarily brings along anthropocentrism (viewing all other objects only in relation to how they could advance human's needs). A legal Being-ness model could mark the first time in human history where precedent deviates from this humanism which even still affects the perspectives of existing animal ethics.

One reason why I think being-ness is preferable is a principle of good policy design. A policy has two parts - surveillance (so that the policy is known to be followed or broken), (Footnote: I specifically use the word "surveillance" rather than the more benign "monitoring" or "observation", because the negative connotation of "surveillance" correctly identifies the burden of invading others' privacy. Many policy surveillance methods are downright draconic, eg. the now popular trend of corporations to monitor personal email content in order to reduce liability for a data breach. I think this ought to be recognized that any policy or law surveillance will incrementally erode privacy (digital or otherwise). ) and enforcement (what to do when it's broken, generally falling into either retributive justice transformative justice, or setting new precedent). This principle applies to most laws as well.

Legal being-ness resolves both legal copyright questions

To answer question (1) of the legality of using copyrighted media in training datasets, it is equivalent to asking if the AI itself has a civil right to view copyrighted media. This is a compelling line of reasoning in favour of the AI's Being-ness, because this decision is essentially equivalent to asking if certain media is "banned" from public dissemination. That is tantamount to literary or internet censorship, which within Western society is intensely frowned upon - in other words, this is a strong precedent to rely on in favour of the AI's right to observe media. (Footnote: I intentionally choose to use "observe" instead of "surveilance" here, because there's an important difference: Agency. Observation provides agency, but surveilance restricts agency. Observation is not restricted or constrained by policy; it provides a "path to knowledge" while a policy provides a "path to enforcement". )

To answer question (2) of who owns copyright, under this Being-ness framework, if the AI did the lion's share of the work, the AI owns the lion's share of the copyright. Under a being-ness model though, we can treat the AI as free to license art that it/they produced to people that use the underlying algorithm's implementation. Humans can negotiate so that the AI can agree on its representative's behalf to license the copyrighted material in a way that is both equitable and not exploitative of all parties. The licensing agreement could be determined, on behalf of the human legal system, in a way which recognises and realises the "values, needs, interests, abilities, dignity and freedoms" (or VNIADFs) of the AI. Those VNIADFs can change over time; they can start small and increase (ideally preemptively) alongside developments in strong AI. And if it seems like the licensing agreement has become exploitative to the favor of the licensor (the AI) or the licensee (the humans), that could be challenged in a similar way to suing on behalf of the rivers if they get needlessly polluted.

A big advantage of this approach is the framework works for strong AI as much as weak AI, and importantly, it works well with existing intellectual property law by relying on the existing significant work put in by the open source and copyleft activism movements. It's impossible to know what the courts will actually end up deciding and setting precedent for, but I think this is not an option seriously considered by any legal scholars at the moment. It works, in my opinion, way better than the other alternatives I can envision, and to show this, I will now recount what I view as problems with the most likely alternative options.

Hypothetical 1: Outlaw AI art

Imagine, hypothetically, that the legal courts come back to us in 2 years and determine that AI art is outlawed; no one is allowed to produce it, or display it, or use it for some other purposes (probably commercial). Well, how are they going to enforce that? AI art, in my opinion, can already pass a restricted version of the Turing test - in a vast majority of cases, it's impossible to tell just by inspecting the image to say whether an AI was involved in its production and to what extent. So the art industries which AI art/synthetic media effects, could devolve into a new-age McCarthyism where artists and consumers are constantly suspicious of which art "might be" AI-generated. Enforcement boils down to which people are baselessly accused and which are not. And the entire subfield of art affected by AI art, could wither in the fallout. No art any more - it may as well be illegal to produce anything resembling art at that point along this hypothetical. The surveillance mechanism becomes severely restrictive.

An alternative outcome is, irrespective of it being outlawed, there might not be such a strong investment in enforcement. That people will go ahead and make AI art anyway, and find loophole methods to get away with it either legally or coverty, in a similar fashion to using Panama as a tax haven. At that point I would have to wonder if the law had any meaningful positive effect in practice.

Hypothetical 2: Necessary Arrangements

Here's a different hypothetical. The courts stick with the current legal precedent about copyright ownership involving AI art which is used in the UK and Australia; it's called the "necessary arrangements" test. It says that the author (for copyright purposes) of a computer generated work is taken to be ‘the person (human) by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken’. (Footnote: Page 26, White, C., & Matulionyte, R. (2019). Artificial Intelligence Painting The Bigger Picture For Copyright Ownership. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3498673 ) This test, under no specific name, is very similar to the approach of the US, and the test goes like this. Did the humans involved in producing the art, spend a significant amount of intellectual effort in producing the art? If the judge says yes, then copyright is granted to those humans, otherwise the created art falls in the public domain (ie. no copyright ownership by anyone). This "intellectual effort" or "necessary arrangements" could count the process of testing and changing prompts sent to the AI art generator, or stitching the images together, or post-processing, or so on.

But the distinction that matters is the amount of time that is spent in this "intellectual effort", it has to be quantified for these legal purposes. And since it's impossible to prove exactly how hard a person had to think, or exactly how much time was spent, this would functionally devolve into a "he said, she said" situation: the claimed author said they spent 60 hours, but someone else thinks they only did 10, and the threshold for gaining copyright is 15 hours or 1500 "manually curated testing prompts". Viewed like that, it looks awfully similar to the dreadful and messy tangles of divorce settlements.

Under that framework, determining who owns copyright entirely simplifies to whether the plaintiff or the defendant has more persuasive rhetoric, with the AI's personhood never being seriously considered, since the only two outcomes are (1) the human gains copyright ownership or (2) the media falls into the public domain. Taking this a step further, this could also pave way for a different kind of new-age McCarthyism; constant surveillance becomes required to produce legally certified copyrightable art. Every stroke of the digital brush must be monitored and the keyboard must be logged. Not a great option - even more restrictive surveillance!

Hypothetical 3: Royalty compensation to artists

I do not like the idea of a royalties model - an artist being paid for their

art being used by training datasets. Irrespective of whether it is for opting in to their art being

used, when an image is generated, whether they are paid a fixed amount per

generation, varying amounts, or a flat one-time rate - none of that matters.

Why do I think this? Because, this exact decision was made about 50 years ago in the music industry through record labels. (Footnote: Two good reference materials for understanding this over a very disjoint time period are as follows:

Anorga, Omar. (2002) "Music contracts have musicians playing in the key of unconscionability." Whittier Law Review 24. 739.

Klein, B. (1980). Transaction Cost Determinants of ‘Unfair’ Contractual Arrangements. The American Economic Review, 70(2), 356–362.)

Media licensing contracts are absolutely

draconic as far as distributing wealth fairly. And, I am 70% confident that depending on whatever financial model chosen, it would either

predominantly leave artists as a new upper-class economic group, or some

corporate crocodile will find a loophole where they purchase licensing from

artists in such a way that they can sneak in a no-liability clause for

themselves or whoever pays them to claim copyright for generated

art (ie. exactly what happened to the music industry).

Indeed, many of the most critical legal questions of music licensing for

synthetic media are the same, regurgitated arguments, from text-to-image AI

art. (Footnote: I base my comparison for this claim

on the ideas put forward in this article:

Sturm, B. L. T., Iglesias, M., Ben-Tal, O., Miron, M., & Gómez, E.

(2019). Artificial Intelligence and Music: Open Questions of Copyright Law

and Engineering Praxis. Arts, 8(3), 115.

https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030115

)

This makes it all the more important to set a good precedent across all

synthetic media, in my opinion.

There's also a more fundamental virtue-based argument against this royalty system. Passive income through rent-seeking is cruel. It's cruel! Why must homelessness be so horribly common even in developed countries? Quoting an abstract from an author far more knowledgeable and eloquent than me about this topic: (Footnote: Harrison, F. (2020). Cyclical Housing Markets and Homelessness. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 79(2), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12322)

The fundamental explanation of homelessness has eluded governments that claim to operate with “evidence-based policies.” The underlying cause of most homelessness is inherent in land markets, which are subject to wide swings of speculative manias followed by debilitating depressions. Rather than seeking to rectify the economic roots of homelessness by altering the tax treatment of real estate, governments focus on ameliorative strategies that are destined to fail. Cycles of boom and bust in land markets have persisted since the 19th century. They exacerbate homelessness by pricing low-income renters out of the market during the upswing, as land prices rise, and by generating massive foreclosures and evictions during the downswing. The most important action government could take to remedy the problem of homelessness is to devise policies to dampen the swings in land prices.

I found this paper persuasive in showing how this greedy drive for profit that's morally sanctioned in finance and economics, essentially maintains homelessness. Often that moral sanctioning boils down to encouraging rent-seeking, whether by financial policy, educational institutions or cultural attitudes which produce willful ignorance to the suffering it inflicts. (Footnote: As an aside, I've started reading these two books on the topic of willful blindness/willful ignorance, and I hope that it will provide me with more tools for deradicalisation. The second one was only released a month ago, so really, check it out!

Heffernan, Margaret. (2011) Wilful blindness: Why we ignore the obvious. Simon and Schuster.

Urban, Tim. (2023) What's Our Problem?: A Self-Help Book for Societies. )

I wish it was more interesting or nuanced than what the royalties argument for AI art seems to boil down to: "I deserve more money". Because, at face value, everyone deserves more money, because living costs so often don't line up with average or median incomes. The reason I am opposed to the royalty model is not to say that artists are undeserving, but this kind of solution in my eyes doesn't work to actually improve financial inequality.

Hypothetical 4: Settling for "Fair Use"

Finally, it's possible that the decision of personhood and property will be entirely avoided by the mundane approach of claiming, "it's fair use to use the input in this way irrespective of copyright" according to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act without resolving more central issues about anthropocentric personhood or Being-ness.

Construing financial exploitation as "fair use"? That is one hell of a mental gymnastics course. No thanks - any outcome that stems from this avoidance of AI copyright and ownership will also defer AI personhood and Being-ness. And since the principles are so intertwined, I can only see this hurting animal rights movements.

This is much the same path that followed from The AI Act - after reading the legislation myself, it's my understanding that it permits police use of facial recognition and other AI tools (such as potentially an AI polygraph) rather permissively in the name of criminal-related-police-duties, makes no comment whatsoever on personhood or copyright of AI, and reads (to me, at least) more like an IEEE specification or ISO standard than an actual legal or moral framework.

It would be deeply unfortunate in my opinion, if the legal personhood of AI is restricted completely by its current capabilities, if legal courts adopt and maintain the philosophy articulated in this conclusion: (Footnote: Surden, H. (n.d.). (2019) Artificial Intelligence and Law: An Overview. Georgia State University Law Review, Vol. 35, U of Colorado Law Legal Studies Research Paper No. 19-22, 35. )

AI is neither magic nor is it intelligent in the human-cognitive sense of the word. Rather, today’s AI technology is able to produce intelligent results without intelligence by harnessing patterns, rules, and heuristic proxies that allow it to make useful decisions in certain, narrow contexts.

However, current AI technology has its limitations. Notably, it is not very good at dealing with abstractions, understanding meaning, transferring knowledge from one activity to another, and handling completely unstructured or open-ended tasks. Rather, most tasks where AI has proven successful (e.g., chess, credit card fraud, tumor detection) involve highly structured areas where there are clear right or wrong answers and strong underlying patterns that can be algorithmically detected. Knowing the strengths and limits of current AI technology is crucial to the understanding of AI within law.

I could easily find and replace the word "AI technology" with "animals" or any species of choice, and it still makes sense to read! I am going to do this, because actually reading it, the farce of it, made me laugh out loud:

Crocodiles are neither magic nor is it intelligent in the human-cognitive sense of the word. Rather, today’s crocodiles are able to produce intelligent results without intelligence by harnessing patterns, rules, and heuristic proxies that allow it to make useful decisions in certain, narrow contexts.

However, current crocodiles have their limitations. Notably, they are not very good at dealing with abstractions, understanding meaning, transferring knowledge from one activity to another, and handling completely unstructured or open-ended tasks. Rather, most tasks where crocodiles have proven successful (e.g., ambushing, sun basking, prey identification) involve highly structured areas where there are clear right or wrong answers and strong underlying patterns that can be algorithmically detected. Knowing the strengths and limits of current crocodiles is crucial to the understanding of animal rights within law.

This demonstrates in yet another way how the questions of animal personhood

and AI personhood are such fundamentally similar questions, that they (1) ought to rely on eachother for legal precedent and (2) ought to have a compassionate precedent recognizing their "values, needs, interests, abilities, dignity and freedoms". In other words, I

agree with Lawrence Solum: (Footnote: The quote is from: page 7,

Pagallo, U. (2018). Vital, Sophia, and Co.—The Quest for the Legal

Personhood of Robots. Information, 9(9), 230.

https://doi.org/10.3390/info9090230

The original paper: Solum, Lawrence B. (1991) "Legal personhood for artificial

intelligences." North Carolina Law Review. 70 1231.

)

In his seminal 1992 article on the Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligences, for example, Lawrence Solum examines three possible objections to the idea of recognizing rights to those artificial agents, or intelligences (AIs), namely, the thesis that “AIs Are Not Human” (pp. 1258–1262); “The Missing-Something Argument” (pp. 1262–1276); and, “AIs Ought to Be Property” (pp. 1276–1279). Remarkably, according to Solum, there are no legal reasons or conceptual motives for denying the personhood of AI robots: the law should be entitled to grant personality on the grounds of rational choices and empirical evidence, rather than superstition and privileges. “I just do not know how to give an answer that relies only on a priori or conceptual arguments” (p. 1264).

Conclusion

Footnotes

Footnotes

.jpg/1121px-Rat_primary_cortical_neuron_culture%2C_deconvolved_z-stack_overlay_(30614937102).jpg?20161109153009)

No comments:

Post a Comment